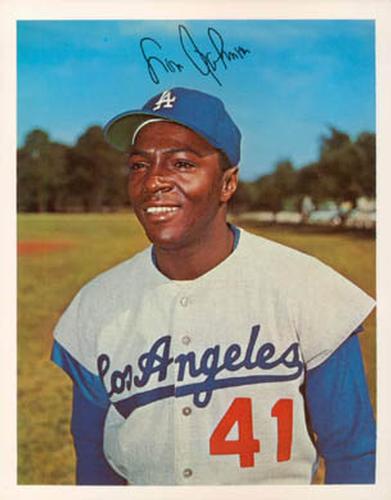

Sweet Lou Johnson Comes Home

By Dr. Daniel Durbin | 8/14/13 |Sweet Lou Johnson Comes Home

It was the most famous (and infamous) fight in Major League Baseball history. Many of the causes are lost in the murky mists of memory that linger still between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the San Francisco Giants. But, on August 22, 1965, the Giants ace pitcher Juan Marichal took a baseball bat to the head the Dodgers catcher, John Roseboro.

A bare few weeks after being called up to the majors to replace Tommie Davis who had fractured his leg, Sweet Lou Johnson, playing left field that day, saw his catcher bleeding from the head and, in his own words, he went crazy.

Sweet Lou Johnson’s road to the Major Leagues had been a hard one. He had played in the old Negro Leagues, bounced around the minors for a decade, and was at the end of his tether by the close of the 1964 season. At the start of the 1965 season, Sweet Lou decided this would be his final shot. If he didn’t make it to the Majors this season, he would give up, move back to Lexington, Kentucky, and find another career.

Sweet Lou always believed he had the talent to be a starting Major League player. But, he had never had the opportunity to get to the Majors and stick. He was pretty sure he knew at least one reason why he had not.

Belying his name, Sweet Lou Johnson may have been baseball’s original angry young man. Sweet Lou discussed that anger and many other subjects this summer as part of the USC Annenberg Institute of Sports, Media and Society’s oral histories project. You can find information about the African-American Experience of Major League Baseball project on the following link.

AISMS African-American Experience in Major League Baseball Research Project

Sweet Lou felt the indignities of open racism and taunting throughout his career. Lou freely expressed his rage.

During that first summer in the Major Leagues, Sweet Lou was asked by a reporter why “you black guys” hit the baseball so aggressively. Sweet Lou responded as if the answer were obvious, “Because the ball’s white. We like to think we’re beating hell out of a white guy.”

The reporter walked away and didn’t come back. For a decade, so had Major League Baseball. Sweet Lou was a man with a reputation.

Sweet Lou’s anger hurt him in other ways. The legendary Buck O’Neil, who coached Lou on the Kansas City Monarchs during Lou’s time in the Negro Leagues, told Lou that his anger got in the way of his play. Buck taught Sweet Lou how to focus his anger, how to use it to become a more efficient and effective baseball player.

With the death of the Negro Leagues, Sweet Lou moved on to the other league, floating from the Chicago Cubs to the Los Angeles Angels to the Milwaukee Brewers to the Los Angeles Dodgers, never really finding a home in the Major Leagues.

Then, in one of the most violent explosions of anger ever displayed on a baseball diamond, Sweet Lou saw his catcher bloodied, his pitcher, Sandy Koufax, threatened, baseball bats in the hands of his enemies and he went crazy. In the next fourteen minutes, Sweet Lou would find the home that had always eluded him.

Running like a mad man, Lou Johnson raced in from left field, looking to punch, kick, in some way beat down anything he found in the orange and black of the hated Giants. He dove into the fray. But, just as he started to flail away, he found his feet coming off the ground and his blows and kicks flying harmlessly in the afternoon sun. The Giants great first baseman, Willie McCovey, had picked up Lou from behind and was holding him in the air.

Sweet Lou would not be able to pour out his years of anger and frustration on the bodies of San Francisco Giants that day. But, he would get some measure of revenge on the entire baseball world that October when he would hit the game-winning home run of the seventh and final game of the 1965 World Series.

Sweet Lou Johnson sat at the top of the baseball world that fall. He was a World Series hero. On the largest stage in his sport, he had shone as few players before or since would ever shine.

One month after the World Series, Sweet Lou would return to his parent’s home in Lexington for a parade that was to be thrown in his honor. As Sweet Lou sat in a car staring out at all the faces, black and white, that cheered him through the streets of his hometown, one thought crept into the back of his mind.

“When I was a kid, I would never have been allowed to sit on the curb of this street. You’d have beaten the hell out of me just for trying.”

The next spring, Sweet Lou Johnson would return home to the Los Angeles Dodgers. Dodgers Stadium remains Lou’s home, to this day. He works with the Dodgers’ community relations program at the ripe young age of 79.

In a sport that barred African-American’s for over half its history and still cannot find the words to truly invite the African-American community into its game, in a city known more for its movie stars than sports stars, an angry young black man from Kentucky found his home.

COMMENTS